The UK grains sector faces enormous change after almost five decades operating under the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy. It also faces enormous potential disruption following the UK exit from the EU on Jan. 31, unless a new trade deal with the EU can be made by the end of the year. At the same time, the sector is coping with the problems caused by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, with supply chains disrupted and new challenges from the need to feed a population in lockdown.

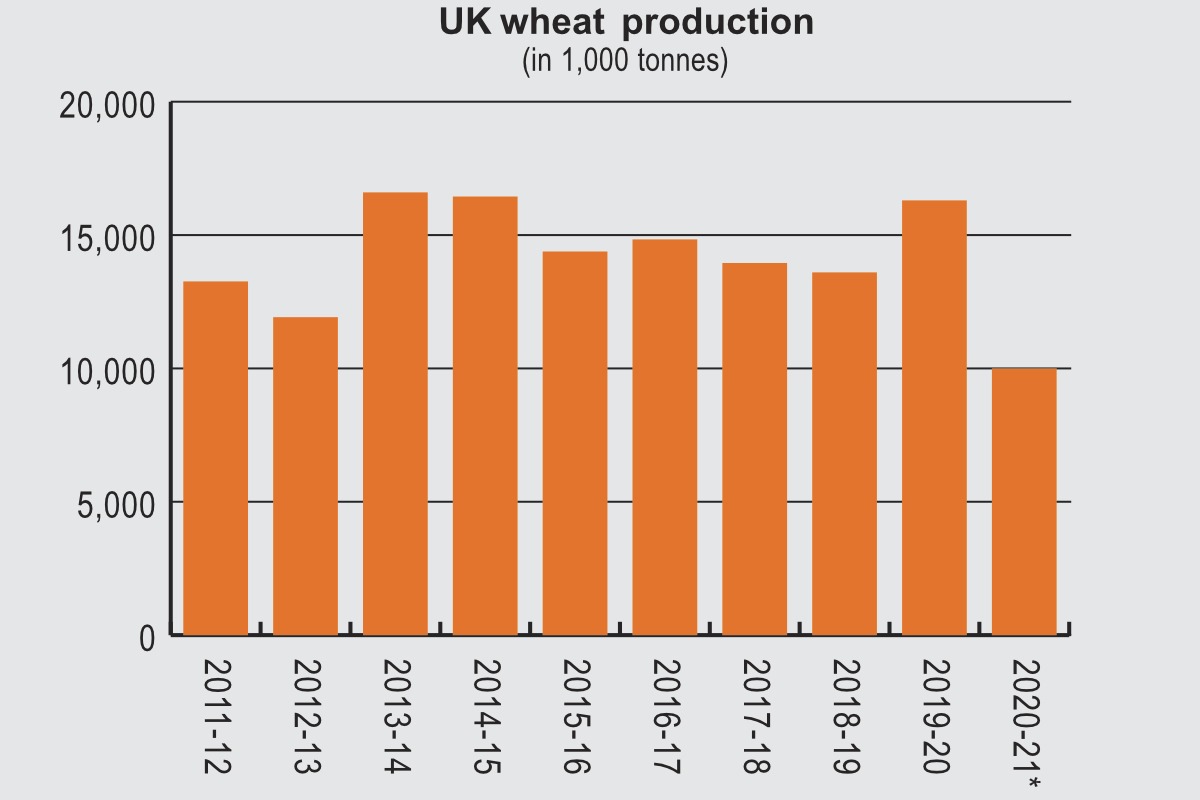

The International Grains Council (IGC) projects the UK’s 2020-21 grains production at a total of 19.7 million tonnes, down from 25.7 million the year before. The country’s wheat production is put at 10 million tonnes, down from 16.3 million in 2019-20. Barley production is forecast to rise to 8.4 million tonnes, up from 8.2 million.

The UK’s rapeseed crop is forecast at 1.3 million tonnes in 2020-21, compared with 1.8 million in 2019-20.

The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) on Feb. 27 published a forecast putting 2019-20 wheat imports at 1.050 million tonnes, down 808,000 on the year before because of greater supply.

“It is worth noting that the fall in imported demand is expected to be driven by the animal feed and bioethanol sectors,” the AHDB commented. “Imported wheat usage by flour millers is expected to be marginally higher year on year.”

The AHDB forecast barley imports at 52,000 tonnes, down 18,000 on larger domestic supply. Maize imports in 2019-20 are put at 2.3 million tonnes. “While the pace of maize imports is expected to slow somewhat over the next few months, imports may begin to increase again at the end of this season and into the 2020-21 season, due to its relative price compared with domestic grains.

Trade sources put likely imports of wheat at 2.6 million tonnes in 2020-21, with barley imports at 60,000 tonnes. Imports of rapeseed are forecast at 600,000 tonnes.

According to the National Association of British and Irish Millers (nabim), there are 32 companies, with a total of 51 milling sites in the country’s flour milling sector. Thirty-one are members of nabim, with 50 sites between them accounting for 99% of UK flour production. The association puts the industry’s annual consumption of wheat to produce flour at 5 million tonnes, with some 1.3 million to 1.5 million tonnes used by starch and bioethanol producers.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown that has accompanied it has forced the industry to change. Following representations from nabim, the government decided to relax working time rules to help ensure deliveries. It also recognized food industry workers as key, giving them access to childcare and education support, the association said in an April 3 statement. British schools are closed but remain open to care for children of key workers.

An early warning system also has been set up by nabim to give notice of problems before they become critical.

“The grain supply and delivery sector, including nabim members, has agreed small changes in working practice that will help the flow of goods and accompanying documentation while respecting social distancing and the difficulty of distributing documentation while so many administrative staff are working from home,” nabim said. “The government has allowed extra time for some tests to be undertaken and, wherever possible, auditing is being conducted remotely.”

One feature of the lockdown has been increased demand from consumers for bagged flour for home baking. A website has been set up by nabim to let consumers know where they can buy the size of bags normally only sold to catering outlets, which are now closed.

The UK left the EU on Jan.31. The country is currently in a transition phase, in which trade continues under the same terms as before, while a future relationship between the two is negotiated. The advent of the COVID-19 crisis means that the transition period, due to last until the end of 2020, is widely expected to be extended, although the British government, which would have to ask for an extension, is still, at the time of writing, insisting that it will stick to the planned timetable.

One aspect of the future that is causing particular concern for the milling industry is the arrangements for trade between the islands of Britain and Ireland. Although the northern part of Ireland is part of the UK, under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which brought piece to Northern Ireland after many years of turmoil, there must be no hard border between the UK and the Republic of Ireland on the island of Ireland. That means that a customs barrier is planned, within the UK. The government of Prime Minister Boris Johnson is pretending that the problem does not exist, and no checks will be necessary, ignoring an explicit reference in the UK’s Withdrawal Agreement with the EU. The high level of integration between the food sectors in the two countries, particularly in milling, means controls, with a potential need for sanitary and phytosanitary checks, could be highly onerous.

Leaving the EU takes British agriculture out of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy, with its system of direct payments to support farming. Instead, in a bill introduced to parliament on Jan. 16, the government plans to create a system under which farmers are rewarded for providing public goods such as improved air and water quality, higher animal welfare standards, improved access to the countryside or measures to reduce flooding.

In England, direct payments will be phased out over a seven-year period, starting in 2021.

BIOFUELS and GMOs

The UK is currently using E5 gasoline, but the government has announced a move to E10, beginning in 2021. The country has two large ethanol plants, Ensus and Vivergo, both in the northeast. Only Ensus is currently operating, using wheat and maize.

In an April 9 report, the USDA attaché in London explained how the British government appears to want to expand the use of GM crops in the country, but the continuing close trading relationship between the UK and the remaining EU countries makes a big change unlikely.

The report cites the July 2019 inaugural speech of Prime Minister Johnson who said: “Let’s liberate the UK’s extraordinary bioscience sector from anti-genetic modification rules.”

“Under any scenario, the UK’s departure from the EU will not change policy or trade in genetically engineered plants or animals in the short to medium term,” the attaché commented. “The EU is the UK’s largest trading partner and the UK will retain much EU food law for many years to come.

“For most of the British public, genetic engineering in food is irrelevant. There are very few mainstream grocery products that contain GE as an outright ingredient and, with this invisibility, UK consumers consider the ‘GM problem’ to have gone away.”

Follow our breaking news coverage of the coronavirus/COVID-19 situation.