LONDON, ENGLAND — The ongoing drone and missile attacks on shipping vessels in the Red Sea by Yemen-based Houthi rebels are starting to significantly impact dry bulk shipments, including grain, after being mainly limited to the container segment during the first stages of the crisis, an International Grains Council (IGC) analyst told World Grain.

The Houthis have been attacking vessels in the region since late October, shortly after Hamas’ surprise attack on Israel, which elicited a powerful Israeli counterattack from Israel on the Gaza Strip, where Hamas is based. The Houthis claim that their attacks on the Red Sea are in response to Israel’s counteroffensive.

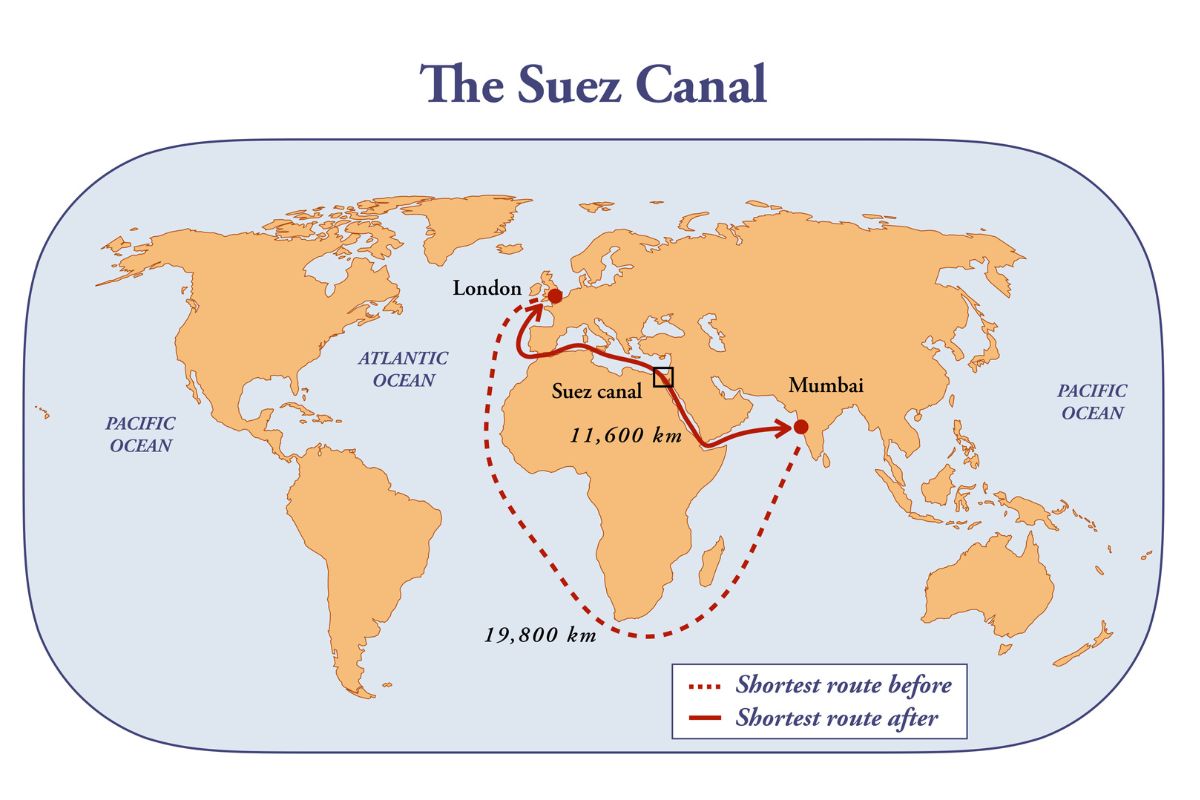

Alexander Karavaytsev, a senior economist with the IGC, said the situation in recent weeks has caused ships transporting bulk commodities, such as grain, to divert deliveries away from the Suez Canal, which connects the Red Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. Citing private, real-time shipping data, he said the volumes of grains and oilseeds transported via the canal during December was 20% lower than the previous month, and well below the same month in 2022 and the three-year average.

Karavaytsev said the IGC has been specifically analyzing wheat flows from the EU, Russia and Ukraine to selected Asian countries and Eastern Africa, which are normally mostly transported through the Suez Canal.

“The portion of alternative (non-Suez) routes for those flows was above normal during December and increased further in January, as preliminary shipping data indicates,” Karavaytsev said.

Credit: ©DIMITRIOS - STOCK.ADOBE.COM

Credit: ©DIMITRIOS - STOCK.ADOBE.COMSeveral of the world’s largest shipping firms — including Maersk, Hapag-Lloyd, and the Mediterranean Shipping Co. — have suspended shipping through the Suez Canal, a move that adds to the journey and the cost of shipping.

Karavaytsev said according to IGC estimates, re-routing from the EU and the Black Sea countries via the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa “adds around 10 to 15 days to the journey time and around $6 to $8 per tonne to freight costs.”

He noted that additional costs are directly correlated with marine fuel prices, which account for about 20% of total voyage expenses, which, in turn, depend on crude oil prices.

Karavaytsev said that with reports of rising demand for marine fuel at ports around Africa, the resulting increase in fuel prices will add to higher freight costs on the alternate routes.

“This could push importers in Asia and parts of Africa to look for alternatives offering shorter delivery times and also exert downward pressure on fob prices in the EU, Russia and Ukraine,” he said. “We have already witnessed some pressure in the Russian market, as well as in Ukraine. In the latter, local exporters are reportedly offering larger volumes of maize to the EU, including for large Panamax deliveries, which are normally used for long-haul trips to Asia.

“With any likely shift in purchases by Asian and African buyers, Argentina and Australia are termed to be well-positioned to absorb some additional demand, as their harvests have now been largely finished. Brazil is also said to be offering some competitive prices, although mostly for feed quality supplies.”

While most grain commodities are shipped in dry bulk vessels, Karavaytsev noted that up to 60% of rice exports from Asia travel by container.

“Costs for containerized deliveries in the rice market have reportedly increased by up to six times on some routes,” he said.

More than 7,000 miles to the west, the Panama Canal, a key waterway for Western grain shippers, including the United States, continues to be plagued by below-normal water levels due to drought. This has resulted in fewer dry bulk vessels navigating through the canal in recent months and larger grain-carrying ships being turned away.

Karavaytsev said he expects the lower-than-normal amount of grain shipments through the Panama Canal “to persist at least through February.”

“The impact of Panama restrictions has been most evident for grains and oilseeds exports from the US Gulf, with some shipments diverted to alternative routes, including the Suez Canal,” he said. “This was the case for US soybeans, with volumes via the Suez spiking in recent months, before plunging more amid elevated security risks and seasonal trends.”

In 2022, ships carrying 36.18 million tonnes of grain — including corn, soybeans, rice, sorghum, barley and wheat — transited the Panama Canal from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and 2.2 million tonnes moved from the Pacific to the Atlantic. Grain is second only to petroleum among commodities that rely on the canal.

Meanwhile, only 14% of the world’s grain and less than 5% of its soybeans pass through the Suez Canal each year, according to an analysis by Chatham House, an international affairs think tank.