KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, US — When one thinks of Russia’s Siberian territory, the image of frozen, snow-covered tundra comes to mind. Yet, in 2020 Siberia recorded its warmest spring and summer on record, with temperatures reaching 100 degrees Fahrenheit on June 19. It was an ominous climate change-related development in many ways as permafrost declined at an alarming rate, a record number of wildfires broke out and the area was riddled with the worst pest invasion in years. However, there appears to be a silver lining for Russian agriculture.

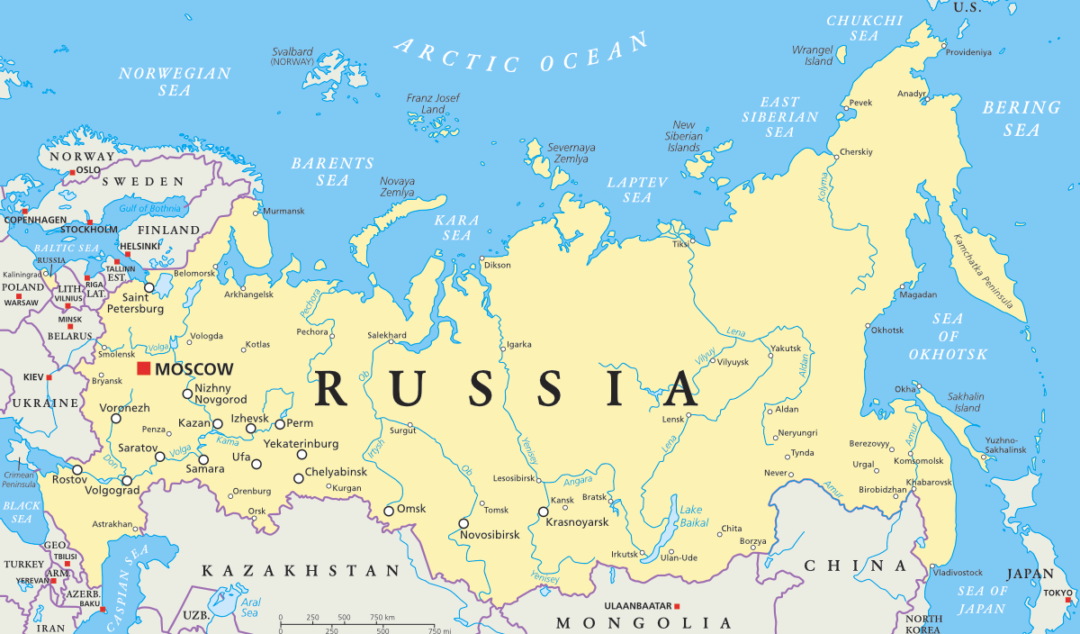

Russia, a country that has transformed itself from a net grain importer 30 years ago to the largest wheat exporter in the world in recent years, stands to gain a considerable amount of arable ground if this warming trend in Siberia continues.

Some projections show that warming may increase Russia’s wheat-suitable land by as much as 4.3-million square kilometers in its northern regions. This could mean more wheat available on the global market, but that assumes Russia will be a consistent grain exporter in good times and bad. The country has a spotty track record in that regard, as it has been known to limit exports not only when domestic stockpiles are low but also for political leverage, so it begs the question: Will having Russia, which is expected to control 20% of the world’s grain export markets by 2028, controlling more of the world’s wheat output be a positive development?

Even more intriguing and hard to fathom than the prospect of expanded wheat acreage is the potential for Russia to increase its soybean output with increased acreage on the vast plains of northern Russia.

China, locked in a trade war with the United States, traditionally its largest soybean supplier, already has purchased land in Eastern Russia to plant and harvest soybeans. Nearly 400,000 hectares of land in Russia is leased or owned by companies with Chinese capital, according to calculations by BBC Russian.

In the near term, Russia will not be a threat to the United States and Brazil soybean producers in terms of Chinese market share. Soybean quality and logistical issues currently prevent Russia from capturing anything but a small slice of the Chinese market. But if the warming trend continues and more acres become available in Siberia, it could tip the scales toward more investment in agronomics and logistics in that region, which over time could make Russia an attractive supplier to neighboring China.

This shift northward of what were previously considered “southern” crops is occurring in all parts of the world. In Canada, for instance, nearly 6 million acres of soybeans were planted in 2019, more than double what had been planted prior to 2009. In Central Russia, the increase in soybean acreage has been 18-fold over the last decade. Even if a large export market doesn’t develop for Russian soybeans, domestic demand for soybean-based feed is growing in the country’s expanding livestock sector.

Much like it was determined to become the global leader in wheat exports, Russia, which is forecast to rank seventh in soybean production in 2020-21 with about four times its production amount a decade earlier, appears poised to become a bigger player in the global soybean market, thanks to an assist from climate change.