It is important for flour millers to identify pathways of microbial infestation of both grain and grain products, recognize the risk of microbial contamination, and encourage taking steps to manage, control and reduce microbial risks associated with grain-based products.

In human food grain handling and processing facilities around the world, considerable time, energy and resources are spent on pest control as covered under Integrated Pest Management (IPM). IPM is considered essential for doing business in developed countries and is making strides in developing countries. Similarly, various food safety programs have become requisite in human food grain handling and processing facilities for both developed and developing countries seeking to meet various food safety program standards.

Human food grain handling and processing operations readily identify birds, rodents and insects in their living form as their focus of pest control activity. In the United States, Title 21, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 110.110 allows the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to establish maximum levels of natural or unavoidable defects in foods for human use that present no health hazard. Reportedly these “Defect Action Levels” are established because it is economically impractical to grow, harvest, or process raw products that are totally free of non-hazardous, naturally occurring, unavoidable defects that pose no inherent hazard to health.

Two defect action levels

There are two defect action levels for wheat flour, including Insect Filth (AOAC 972.32), an average of 75 or more insect fragments per 50 grams of flour, and Rodent Filth (AOAC 972.32), one or more rodent hairs per 50 grams of flour. The defect source for insect fragments is reported to be pre-harvest and/or post-harvest and/or processing insect infestation. For rodent hair the defect source is identified as post-harvest and/or processing contamination with animal hair or excreta. The significance of the defect action levels identified for wheat flour is reported as aesthetic or offensive to the senses. Given health risk recalls associated with grain-based product and the inability to rule out all potential sources of contamination, the significance of the aforementioned defects is not so much aesthetics but rather a food contamination risk.

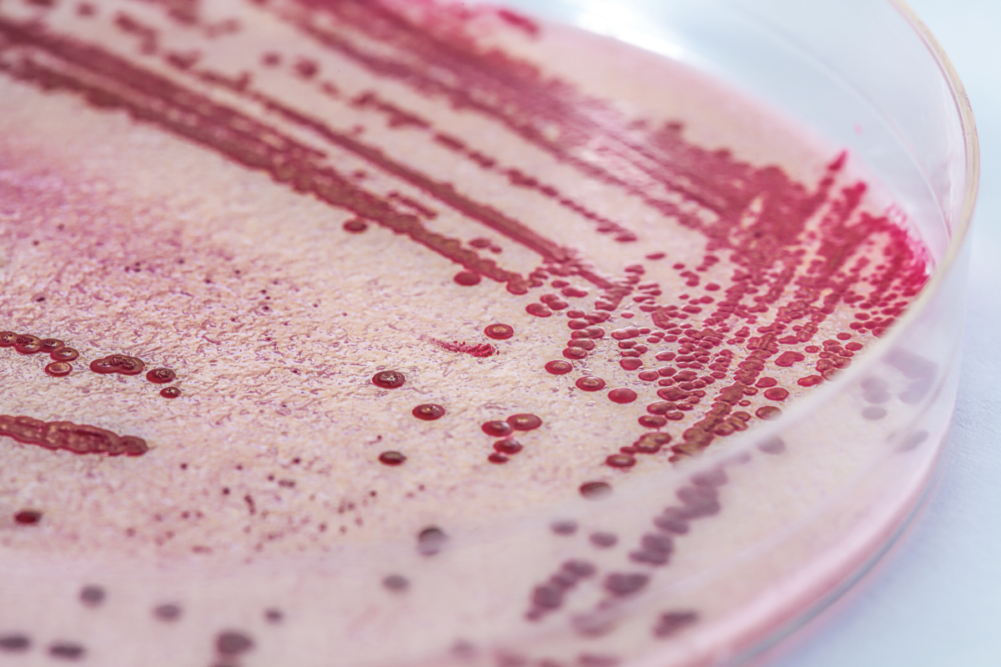

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identifies rodents, including rats, mice, voles, muskrats, ground squirrels and beavers among potential sources of Salmonellosis, Rat-Bite Fever, Plague, Omak Hemorrhagic fever, Lymphocytic Chorio-meningitis (LCM) Leptospiriosis, Lassa Fever, Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome and Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome. These diseases are of bacterial and viral origin spread by various means such as soil, dust or water contaminated with rodent droppings, urine fecal material. Birds and their droppings may carry over 60 diseases, many of which originate in bird droppings and can become airborne and land in or on food or water supply, including Histoplasmosis, Candidiasis, Cryptococcosis, Salmonellosis and E. coli. Additionally, birds are associated with 50 kinds of ectoparasites of which approximately 66% may impact humans, including Yellow mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) found in grain or grain products and may cause intestinal canthariasis and hymenolespiasis.

Insects carry on or within their body’s bacteria and other microbes capable of causing disease. Flies, cockroaches and even the common ant often come from pathogen-infected sites transporting pathogens to products destined for human food production. Moths and beetles that live in dry cereal foods or in whole grains are capable of transporting fungal spores as well as other microorganisms, including pathogens from areas of active grain spoilage, including damage, decomposition and rot.

To perform well within established Defect Action Levels, grain handling and processing operations focus on the primary control method exclusion to protect both grain storage, processing and finished product storage area from intrusion and proliferation of birds, rodents and insects. Cleaning, chemical and/or heat treatment may be employed where infestation or the establishment of an active pest breeding population is evident.

Birds, rodents and insects, whether alive or dead, in whole or in part, along with some life process byproducts, including solid excreta, can be removed to some degree using typical grain cleaning principles. These readily identified pests also host and transport smaller insects such as mites and lice in addition to microbial contamination, including non-pathogens and pathogen, yeast, molds, and fungi. The presence of microbial contamination carried on the intruding pests or in excreta, urine or shed body features such as feathers, hair, dander or cast skin may well contribute to increased microbial contamination of wheat already subject to contamination during field growth and harvesting. Raw grain is receiving significant attention relative to fungal contamination and mycotoxin presence. However, less attention is being given to other microbial and particularly pathogen issues.

Proper design is helpful

The design and operation of grain handling and processing systems had seen much improvement in recent years, including designs to exclude pests and to make food contact surfaces more accessible for cleaning. Elimination of static product within the process and pieces of equipment has been of great benefit. More extensive use of aspiration and dust control has transformed mills from having dirty cleaning house operations alongside clean milling operations.

In recent years, some milling machines such as sifters have been re-designed to prevent condensation and mold development. While more intensive scouring is reported to reduce microbial presence in wheat cleaning, equipment has not yet been developed to remove extraneous material that may be a source of microbial contamination lodged in the crease of some grains, especially wheat. The inability to address the wheat kernel crease is an important issue as data suggests a significant proportion of microbiological activity is associated with the bran coat.

Table 1 shows the microbiological analysis of mill feed and straight grade flour milled from commercially cleaned wheat, which suggest bran carries a significant proportion of wheat kernel microbial contamination. Not all grain milling sites enjoy the benefit of improved system and equipment design available in recent years.

Still today, many grain-based processing systems are their own worst source of potential pathogen contamination due the presence of pathogens in raw materials and condensation allowed to form inside processing equipment. Table 2 shows the relative humidity and temperature differential that allows for condensation to form. Condensation supports microbial growth and development, which may be a source of contamination of product moving through the process.

The focus on microbiological contamination in grain handling and processing facilities has been in the area of reducing human contact with food product. In addition to personal protective equipment such as safety glasses, hearing protection and gloves, employees in most departments and craft areas are now required to wash, dry and perhaps sanitize hands upon entering the facility as well as change into shoes and clothing, including hairnets, masks and gloves reserved for on-site processing and packaging areas to prevent microbial contamination and reduce risk of pathogens in finished product.

Samples once collected in bare hands and returned to the process following inspection are now collected with clean tools, inspected and disposed rather than reintroduced into the processing system. All of these efforts are considered necessary primarily to pass plant sanitation inspections and to a lesser degree prevent microbial or contamination of food product by human operatives.

Processing and packaging

Processing and packaging of potentially pathogen containing grain product has become more important as the risks have become more evident. At one time, flour and other grain products were almost always processed through a kill step either in a commercial facility or at home, thought to eliminate pathogen risks associated with the grain-based product. Undoubtedly, employees or consumers may have tasted product in process and suffered few, if any, consequences connected with the grain-based food product. Grain-based products increasingly are used in packaged cake and cookie mixes, refrigerated or frozen dough, including biscuits, pizza dough and cookie dough ice cream products increasing the probability that the product is tasted or ingested prior to any baking or heat treatment that constitutes a kill step. Food processors and consumer awareness is ever increasing, and the bar is being raised relative to their expectations of pathogen-free products in every aisle of the grocery store, including the baking aisle.

Over a decade ago, students in my Mill Processing Technology Management class in the Department of Grain Science and Industry at Kansas State University were warned that one of their biggest issues would be addressing microbial pests in their facilities. It is a paradox that the largest pests we spend resources on to control in the grain processing industry are ones that can be easily seen, while the pests not easily seen, microorganisms and pathogens, have the potential to cost dearly due to recalls, litigation and consumer health.

Milling organizations, especially those with consumer brand identity, should be looking for pathogen mitigation technologies and implementation before the consuming public, industrial customers, or government agencies intervene.

To view the tables referenced in this story please visit our November digital edition.

Jeff Gwirtz, a milling industry consultant, is president of JAG Services Inc. He may be reached at [email protected].