Australian grains production is set to bounce back in 2020-21 after suffering from reduced output for several years due to drought. The country is a major player on the world market, with much of its grains and oilseeds sector focused on export.

The International Grains Council (IGC), in its Grain Market Report of Sept. 24, forecast Australia’s total grains production in 2020-21 at 43.3 million tonnes, up from its figure a month earlier of 41.6 million. The previous year’s total crop was 25.7 million tonnes.

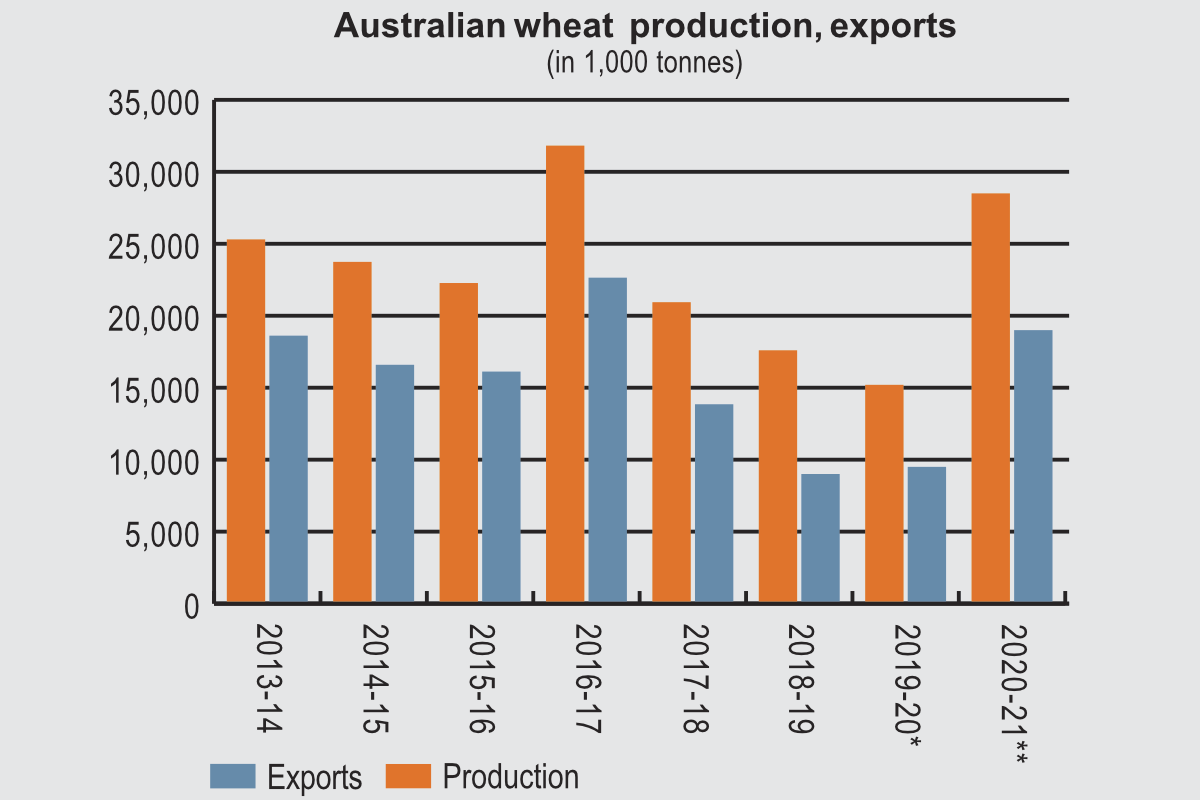

The country’s 2020-21 wheat crop is forecast at 28.4 million tonnes, up from 27.5 million predicted a month earlier and compared with 15.2 million the previous year.

Production of corn is seen at 400,000 tonnes, unchanged from the previous estimate and up from 200,000 tonnes the year before.

Barley production in 2020-21 is now put at 10.9 million tonnes, compared with a previous forecast of 10.5 million and up from 9 million the year before.

For sorghum, the IGC forecast is 1.7 million tonnes, up from the earlier estimate of 1.4 million and 300,000 tonnes the previous year.

Australia also will produce 1.7 million tonnes of oats, revised up from 1.6 million, compared with 900,000 the previous year.

Its total 2020-21 exports of grains are forecast at 21.8 million tonnes, up from the IGC’s previous figure of 19.9 million and also up from 13.4 million in 2019-20.

Wheat exports for 2020-21 are put at 17.9 million tonnes, up from the earlier forecast of 16.2 million, and up from 10.1 million the year before.

The IGC’s forecast for Australian barley exports in 2020-21 is 3.4 million tonnes, including 1.9 million for feed and 1.5 million for malting, up from the earlier forecast of 3.2 million (1.7 million feed, 1.5 million malting). The previous year’s barley exports were 3 million tonnes, 1.5 million feed and 1.5 million malting.

For sorghum, 2020-21 exports are now forecast at 250,000 tonnes, down from an earlier estimate of 330,000, compared with 72,000 the year before. Exports of oats are forecast at 250,000 tonnes, an unchanged figure, with the previous year at 185,000 tonnes.

The IGC forecast Australia’s 2021 rice exports at 100,000 tonnes and does not give a figure for 2020. It expects the country’s rice production to rebound to 186,000 tonnes in 2020-21, from 37,000 the year before, although it notes that this level is “significantly below past peaks as rice continues to compete with alternative crops for water allocations.”

Australia’s 2020-21 rapeseed production is forecast at 3.3 million tonnes, up from the previous forecast of 3.2 million and compared with the previous year’s crop at 2.3 million. Its rapeseed exports are forecast at 2.2 million tonnes, an unchanged figure, and up from 2019-20 rapeseed exports of 1.7 million tonnes.

“Beneficial and widespread rainfall in early 2020 has increased prospects for a good start to the Australian grain sowing season,” the USDA attaché explained in an annual report on the grains sector dated April 21. “This follows two years of below-average grain crops as a result of drought conditions in eastern Australia.”

The report outlined the big regional difference in wheat supply and use and supply chains between Western/South Australia and eastern Australia.

“The wheat industries in Western Australia and South Australia are almost completely export focused, and typically more than 85% of the wheat production in these two states is exported,” the USDA said.

“This is because there is limited domestic consumption of wheat (such as flour milling and intensive livestock production) in these areas,” the agency added. “For example, although these two states account for well over half of wheat production, they also account for just over 10% of cattle production. Much of the wheat growing areas in these states are close to export ports, and the infrastructure and supply chains in these states are directed toward exports.”

The report explains that six of the seven largest wheat export ports are in those two states.

“In addition, in South Australia especially, export infrastructure continues to expand, such as a new facility on the Eyre Peninsula which is about to come online and will be used to transship grain into large vessels for export,” according to the report. “Finally, because of the strong export focus and low storage prices from the major bulk handlers, there has not been extensive expansion of on-farm storage in these two states.”

Eastern wheat growing regions such as New South Wales and Queensland, however, are much more domestically focused, the attaché said.

“Only about one-third of the wheat grown in these states is exported (and during the drought exports have been nearly non-existent), and there is much greater domestic grain use,” the USDA said.

Those two states have the majority of Australia’s feed lots and much of its milling sector.

“Also, because of the robust domestic demand here and more marketing options, there has been a very strong increase in the construction of on-farm storage, and total storage (bulk and on-farm) in these regions now greatly exceeds typical harvest volumes,” the USDA said. “Industry expectations are that the strong domestic demand for wheat in eastern Australia, especially from the livestock industries, will continue in the long term and so any future expansion in wheat exports from Australia will likely need to come from Western and South Australia.

“Victoria is the other major wheat producing state and is a mix of these two regions, with some milling and wheat feed consumption, but also strong exports. Typically, about half of wheat in Victoria is exported.”

For wheat, the report explains that this year “higher production coupled with reduced feed demand would allow for greater export availability, and Australian wheat is expected to return in greater quantities to some key Southeast Asian markets.”

“Exports are also likely to be supported by a continued weak Australian dollar compared to the US dollar,” the USDA said. “Australia is typically between the fourth and sixth largest wheat exporter in the world.

“Second, although wheat yields were poor last year, barley yields were actually about average for Australia as a whole. This was due to a bumper barley crop in Victoria, and key barley areas in Western Australia having relatively better growing seasons than the wheat areas.

“There is a limited amount of barley used in ethanol production in one plant in Australia, although sorghum is the primary feedstock in that facility.”

Second largest canola producer

The attaché explained in a separate report on the oilseeds sector that “Australian oilseed production in marketing year 2020-21 is forecast to begin to recover following years of drought-impacted crops.”

“For canola, higher prices and much better soil moisture at planting are expected to result in an expansion of planted area,” the report said. “Canola is an important part of the crop rotation with grains such as wheat and barley. Due to its higher rainfall requirements, it is predominately grown in higher precipitation wheat-growing areas.”

It is estimated that about a quarter of the canola crop is genetically modified and GM and non-GM canola are kept segregated for different export markets, the USDA said.

“South Australia is the only major canola-producing state that has had a moratorium on GM plantings in recent years,” the report said.

“Although the South Australia government has announced a plan to remove this moratorium, if and when this may go into effect is not yet clear,” the USDA added.

Australia is typically the second largest canola exporter (after Canada), accounting for about 15% of global trade on average, the report said. About two-thirds of exports go to the European Union (EU), primarily for the biodiesel market.

Consolidating milling industry

According to the Australian Technical Millers Association, (ATMA) the number of Australian mills “has declined to the order of 28 spread across all states and situated in both metropolitan and country areas,” from more than 500 in the 1870s.

“This continuous trend of fewer but larger capacity mills with fewer employees is common to countries with highly mature milling industries,” the association said. “However, with the growth in Australia’s population, demand for flour products at home has increased steadily.”

It puts annual domestic human consumption of flour at around 1.5 million tonnes with a further 440,000 used for industrial purposes such as starch and gluten.

Total flour production of around 2.6 million tonnes represents an increase of 26% over 10 years.

“Of the flour sold for human consumption, just over 60% is used by specialized commercial bread bakers,” the ATMA said.

Chris Lyddon is World Grain’s European correspondent. He may be contacted at: [email protected].