GRAND ISLAND, NEBRASKA, U.S. — Several factors are challenging the current grain merchandising model, and traditional grain companies will have to transform themselves quickly if they want to succeed, according to a new report from Rabobank.

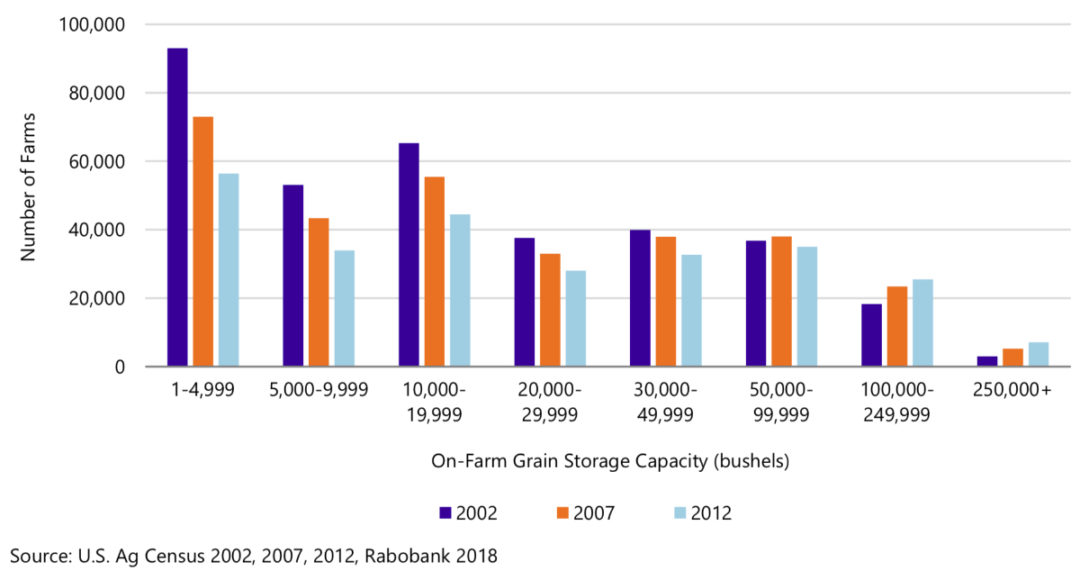

The report, “U.S. grain storage and challenges to traditional grain merchandising,” said it’s not just on-farm storage and producer marketing patterns that challenge the long-term viability of the existing merchandising model. Those reasons are often given as explanation by large and small grain companies for poor earnings.

Stephen Nicholson, senior analyst of grains and oilseeds at Rabobank, said in the report that the situation is far more complex.

“Contributing to a squeeze on margins are also the concentration of grain origination assets and storage capacity at the top grain companies, increased competition for grain in the country from many end users, sector players with different objectives and business models, increased competition for export business and more nimble players,” Nicholson wrote in the report.

A smaller number of producers are controlling a large amount of grain and are effectively cutting out the elevator in the middle. As such, they control production, logistics and storage, the report said, and become a viable seller to processors and export facilities.

“In other words, they become a direct competitor to the ABCs,” the report said.

At the same time, major grain companies are controlling a larger portion of grain origination assets. Yet they are still experiencing profitability challenges.

There is increased competition for grain with processors, exporters, large livestock operation and export terminals all competing for grain.

New entrants into the market are strategically located and can attract grain by paying higher prices to bypass the local elector.

“These facilities tend to be more flexible, nimble, opportunistic and they fill niche market needs,” the report said.

Other new players have entered the U.S. grain market with the goal of sourcing for their home country. Examples include Zen-Noh and COFCO’s purchase of Noble Grain and Nidera.

Increased competition in export markets is another factor. More grain and oilseed production in Brazil and the Black Sea are challenging the U.S. export status and lowering commodity export prices in the world market.

Solutions for the grain merchandising business likely will be found outside of the sector, Nicholson said.

He said the future will include producers controlling more of the supply chain and a closer contractual relationship between the producer and end user.

To stay relevant, grain originators/handlers/merchandisers will have to simplify their business models, re-establish trust with the producer customers, increase traceability, have closer relationships with customers, be more customer-service-oriented and be flexible.

Nicholson had a similar list for how grain companies will have to respond to a new marketing environment. They will have to look beyond their core grain business and expand along the supply chain such as into processing or becoming a fully integrated food company.

They will have to adjust to digitalization on farm and in the chain to deliver extra value, Nicholson said. Companies should also prepare for higher traceability from farm to fork and optimize grain origination asset networks and handling capacity.

Lastly, they should evaluate on-farm grain storage financing options, especially as more U.S. soybeans need to be carried longer through the season.

“The marketplace is changing how and where grain moves to market and therefore changing the grain companies’ business models,” Nicholson said. “As their business models change, assets deployed will change, ownership of assets will change, and ultimately the prices paid and received with change. The changes are just only beginning.”